Hi again.

Here’s a story about something that happened to me and my friends exactly ten years ago this month. It’s a long one but it’s a good one.

***

When we made it to breakfast on time that morning it felt like a victory. We walked back from the lodge to the open lot where we had parked the van the day before, on the recommendation of C’s friend, who was working in Yellowstone for the summer. There were five of us—me and my boyfriend, C and his girlfriend, our friend K—and we had been on the road for about ten days at this point. We had already seen a music festival in Michigan, and the highways of the Midwest, and some of a Great Lake, and the Badlands. We had about two weeks ahead of us, where we’d see Grand Teton and the Redwoods and San Francisco and several bears and a moose, where we’d sleep on friends’ floors and talk for hours around campfires and listen to all our favorite songs and survive a handful of arguments and laugh until we cried. We didn’t precisely know all that then, though. We just knew we had time.

When we had arrived in Yellowstone the previous day, all the campsites had already been spoken for, since July is peak camping season in the National Parks. But we were determined to stay for a couple days, at least. So the friend recommended we spend the night in our van, in the parking lot between her dorm building and a set of rental cabins. (The cabins were, naturally, already booked up.) We had enough space in the 13-passenger van for everyone to sleep; we’d done it before. It was a good enough plan.

We spent the day exploring. We saw Mammoth Hot Springs (“underwhelming, but I didn’t mind,” I wrote in my journal). I got a nosebleed. We got to shower in the friend’s dorm—a godsend—and then she took us to the Yellowstone employee pub, where she worked. It hadn’t occurred to me that the National Parks Service would provide things like this—dorms, an employee pub—but it made working there seem so charming. Like summer camp.

We went to the pub exhausted but exhilarated. At this point, the five of us were all getting along reasonably well: making plans for each day together, sharing the driving and the cooking, indulging each other’s roadside interests. On travel days I mostly spent my time in the first row, driver’s side. I wrote a lot, read a little bit, chose the music occasionally. I had baked a vat of granola before the trip and seemed to be the only one eating it. The boys bought packs of cigarettes in states where they were cheap. We had a big cooler for food in the back of the van, plus a huge receptacle for water, plus a smaller cooler for booze: cans of beer, bottles of whiskey.

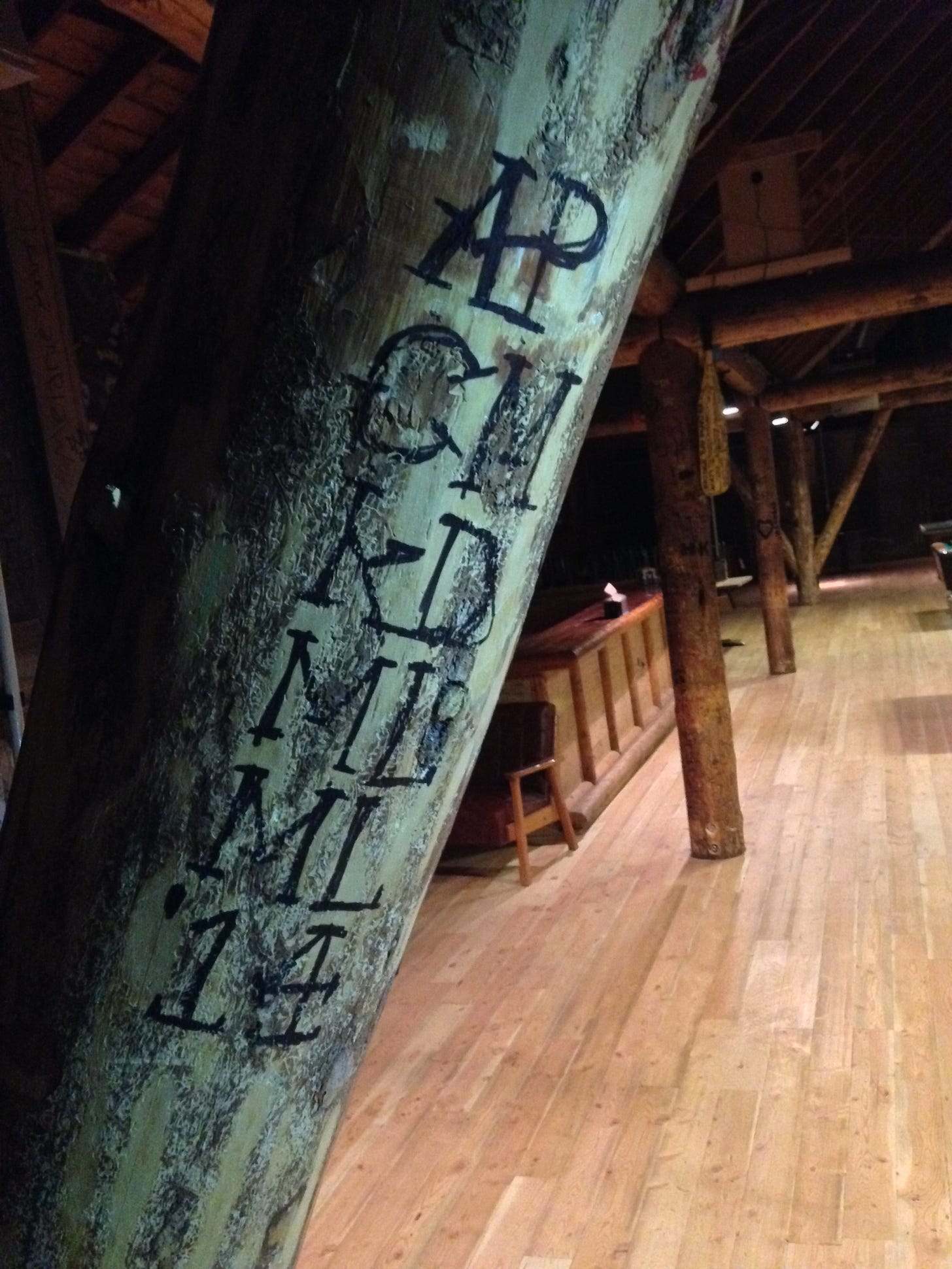

At the pub we got drinks and shouted to each other over the loud music, retelling inside jokes from the trip so far, making plans for the future. We added our initials to a post where many people before us had also written theirs. We made some new friends and asked them endless questions about working in the park; I kept saying, over and over, how beautiful they all were. Most of the exact details of the night have since faded from my mind but I remember smiling ear to ear, and I remember a feeling of togetherness among the five of us, a closeness fostered by the newness of it all. We stayed until last call and then walked back to the van buzzing, electric, overjoyed. The five of us climbed into the van and turned on the engine so we could keep listening to music. We sang along to Robyn, which had become a daily tradition for us. (It had started as a lark, an inside joke—someone played her songs one day, then someone else requested them the next, and then the next, and eventually we kept to it, like a daily religious practice.) After listening to music for a while we got tired—maybe around one or two a.m.—so we turned off the van and lay down on the bench seats and slept.

I don’t remember sleeping particularly well, though I know we slept late. So we were thrilled to have made it to breakfast the next morning, just before the lodge stopped serving it and turned over to their lunch offerings. It felt fortuitous, fated. “I feel like this is a video game, and it’s like … you know … I’ve reached a new level,” K tried to explain, caffeinated but still drowsy, as we walked back to the van. It was then that we noticed the boot. Rear wheel, driver’s side. The van was effectively trapped. Fate had taken a turn.

We were freaked out—what had we done to deserve the boot?!—through I recall a certain haste with which we sprung into action. There was a phone number for the park rangers, so we called it; they said they’d send someone to assess the situation. We prayed the whole thing wouldn’t be expensive. I prayed we wouldn’t get in trouble, though to be honest it did seem a little late for that prayer.

While we waited, we searched the van for anything incriminating; removed it. We picked cigarette butts up off the ground (which we had been intending to do anyway before we left, thank you very much—even the ones that weren’t ours, which comprised most of them) and threw them in the trash. K himself was a liability; just a week before we left for this trip, he had misplaced both his driver’s license and his passport. With no way to prove his identity, we figured he should not talk to the park cops. He hung out in the dorm.

Two rangers showed up, a man and a woman. (These were not the same type of friendly park employees we had met the night before; these were, we realized, ambassadors of a federal department, officers of the law.) They explained the problem: someone in one of the cabins had called in a noise complaint overnight. (A memory resurfaced for me, right then—a stranger had yelled out to keep it down when we were walking back to the van.) We weren’t allowed to camp in the parking lot, the rangers told us, and when they had come to question us that morning about the noise and the van, we were nowhere to be found. Hence the boot. Did we mind if they searched the van? We all had an inkling that we didn’t have to say yes, and I’m not entirely sure we did, though we thought perhaps it would mean they’d be out of our hair sooner. They claimed that earlier, they had seen, through a window, a half-drank bottle of booze. An open container was a serious offense. We said we didn’t know anything about that. They claimed there had been litter. We looked down at the ground innocently. We didn’t see any litter.

It was drizzling. We were made to stand several feet away from the van. One officer searched the van while the other tried to chat with us. My friends and I spoke as little as we could get away with, sneaking glances at the van, trying to get a sense of what the other officer was doing. It was tense; I felt nervous, and I could sense my friends’ anger. My stomach kept turning over and over and over. I wasn’t sure what the worst-case scenario was, but I tried to keep my mind from wandering towards those possibilities. In the end, after another lecture, they handed us each three pieces of carbon-copied paper. Our crimes: littering, camping out of bounds, disorderly conduct. The whole thing felt preposterous and devastating, though in terms of the charges I personally felt that only littering carried a moral stain. We were given a court date in September, and were told we could likely appear over the phone.

We were all aware that it could have been worse, that park rangers and the like routinely treat people much more harshly for much smaller offenses. Still, we were indignant about the whole situation—that we had gotten screwed for something so minor; that, since we were on federal land, the charges and their potential consequences weren’t entirely insubstantial. And the rangers had acted so serious about it!, we said to each other afterwards; it was, we all agreed, not that serious. Still, I—admittedly sheltered and uptight, a self-described rule-follower—felt horrified. Later, when I told my parents what had happened, they were sympathetic but found my reaction a bit dramatic. One day this will be funny, my dad said, and I—fuming on the other end of the phone—silently swore that it never would be. I was afraid that getting several tickets from a park ranger would come to define my life, in a legal-consequences sense, or would come to define the trip, either by bumming us out for the rest of our travels or by tarnishing the memory.

But after some cathartic group venting, the trip continued as planned. We saw Old Faithful, got out of Yellowstone, drove west. My indignant attitude faded. I read Cool For You on the highway through Idaho, and we went on to Portland and the Redwoods. And on and on. Eventually, we drove home in a straight shot from Colorado. I remember trying, at the very end, to hold onto the feeling of the trip as the hours ticked down and the East Coast drew nearer.

Weeks later, all of us back home, we did our phone court appearances. We paid fines; we put the situation in Yellowstone behind us. With a little time and distance (and luck and privilege), it became clear that none of my fears would come true. It goes without saying that my dad wound up being right: of course the story is funny now. When I was 22 I got a bunch of tickets in a national park for singing Robyn too loudly! For having too much fun with my friends! I still talk about this trip all the time, and mostly I only reference that fateful day with the rangers in passing, or as a funny story. Mostly I think about how beautiful the trip was, how much I loved seeing those landscapes, how I was on the verge of an entirely new phase of my life and I could feel it. How good it felt to hold all that wonder and eagerness and exhilaration in me—how that changed something in me. “I like myself here,” I wrote in my journal a week or so after leaving Yellowstone, after a day spent hiking in Zion. “I was waiting for a giant flash of inspiration to change my life. But maybe it is in the small, subtle ways, like this, that the shift is taking place.” She was right.

***

Here are some other things I have been consuming lately: two albums I reviewed for Pitchfork: Charm by Clairo and Revival of a Friend by Sour Widows; Flock of Dimes and Pedro the Lion at Music Hall of Williamsburg; Ekko Astral and Lambrini Girls at the Sultan Room; this article about having a bad memory (I have a terrible memory); this strange and moving short story in Granta; the movie School of Rock, for the first time ever—as good as everyone says, lol; several days in England (in Brighton and Manchester specifically); a preview of the forthcoming book How Women Made Music, drawn from a project I used to work on at NPR—it’s so good and you can pre-order it!; a frozen tahini cold brew from Textbook in Bed-Stuy; this amazing current season for hydrangeas

***

This time last year I was: asking my friends for timeless endorsements; and before that: considering limits, thinking about emo, and submitting to art

***

Thank you for reading. While writing this newsletter, I went back and re-read my journal from that road trip in its entirety. Reading it was—not to be corny—a pretty profound experience! There is so much more I could say about that trip but I will cut myself off here. Anyway, if you have any souvenirs of yourself from a decade ago, or from when you were 22, or from a similarly transformative moment, I urge you to take a look. That person is still in you, and look at where you are now: you took such good care of them. I hope you’re proud.

Until next time!

xo,

M

In 1985 I drove from NJ to California with two cars full of friends, with a long stop at Yellowstone. We camped legitimately, but torrential rain gave us the great idea to all cram into the larger car, find a parking lot near geysers, and watch the intermittent burbling. And smoke joints and listen to the Grateful Dead. Anyone walking or driving by would surely have heard the music and seen the car absurdly full of smoke. Nobody cared though. Another era, or were we just lucky?

this was such a lovely story. i feel like the expansiveness of nature and feeling free inside of it really does do something profound to someone.