constellations #61: finding the zero

Hi again.

When Matt and I lived in Washington, D.C, we were often on the road late at night. A few times a year, we’d drive back to Massachusetts to visit our families and usually this meant leaving work at 6 p.m., packing up the car, and driving for eight or so hours straight up 95, trying not to wake our parents when we got in. At this time of year, it was always closer to a ten-hour drive, the roads clogged with people like us. I usually found these late-night drives romantic in theory and difficult in practice, but he loved them unequivocally. When I think about those drives now, I think about being alone on a small scenic route north of New York City, quiet, headlights on the highway, Matt cracking a window every so often to smoke a cigarette.

(When I was twenty-two, I had some of the best drives of my life. We took a road trip across the country and often spent the night driving. The first day we drove overnight to Michigan, and later we drove overnight between the Badlands and Yellowstone, and at the end of the trip we drove in a straight shot back to the East coast from the mountain West. Sometimes I couldn’t fall asleep because I was so full of joy, surrounded by friends, headlights on the highway.)

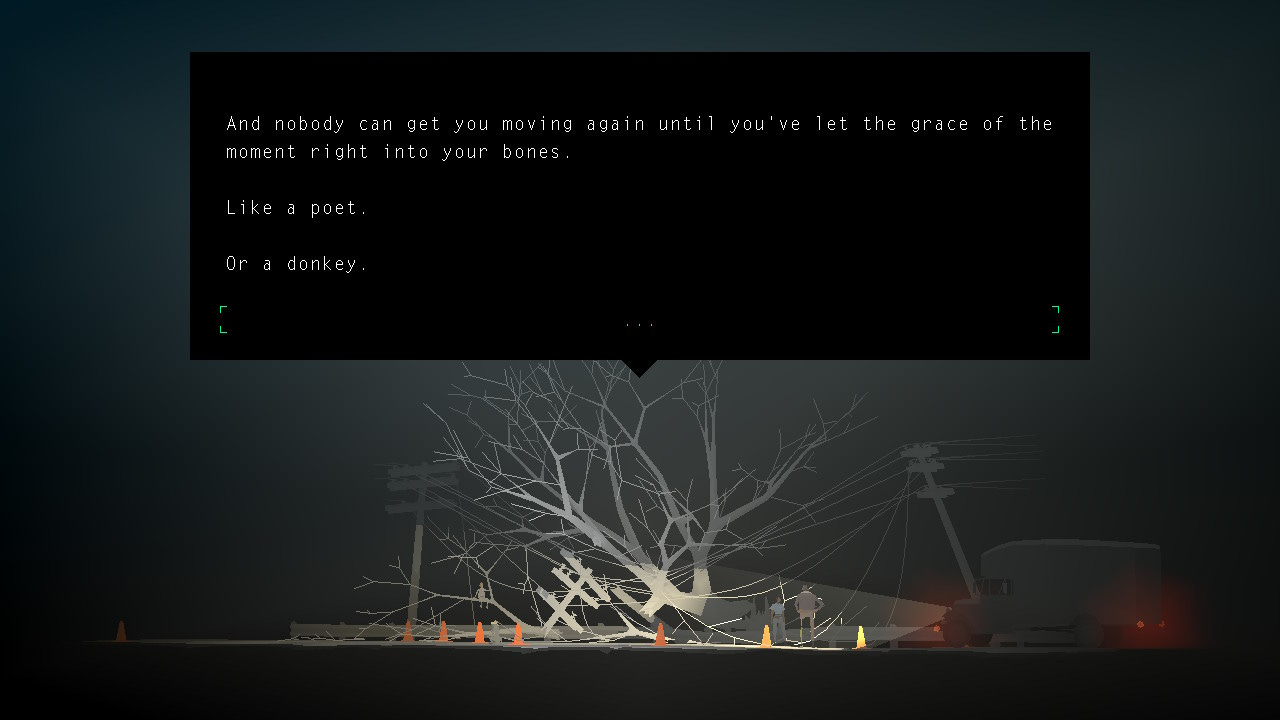

This past month I have been driving in the dark again, on a strange underground highway in Kentucky. Except this highway is a fictional place: the titular road from Kentucky Route Zero, a point-and-click magical realist adventure video game, released by Cardboard Computer in five acts over the course of seven years.

The highway has taken me to the unmapped caves of the Echo River, to a grand retrospective for a conceptual installation artist, to an avant-garde theater production, to a nearly drowned community television station. The game is about a delivery driver for an antique shop who’s making his final trip, but it is also about loneliness and addiction and debt and gentrification and joy and music and community and the power of art.

Sometimes, when I’m driving in the real world, I feel like an open book. It feels like if I’m focused on the road I can’t also focus on a narrative, and if someone asks me a question my defenses are down. Like I don’t remember how to give a convenient or useful or strategic or even eloquent answer, or draw an example to illustrate a point, or articulate something complex — just a direct line to my lizard brain, or something. The first time I remember this happening, someone I had a reluctant crush on, who had accidentally set the GPS to avoid all toll roads, was in the passenger seat. It was a long drive.

Getting on The Zero isn’t terribly straightforward: You have to go through an abandoned mine, fix the image on a broken TV, find the right kind of static on the radio. You have to be tuned to the right frequency, I mean. I think I had to be tuned to the right frequency, too. I’ve been promising Matt, who played each act of Kentucky Route Zero as it was released and truly loves the game, that I’d play it for years. But I (not really a gamer*) avoided it — mostly, honestly, because I assumed that I’d be bad at it, and then I’d be committing to spending my leisure time failing at something. I finally sat down to play this month when my leisure time started giving me a quiet sense of panic: the sun setting too early, my brain feeling too fried for the books I was supposed to want to read, my TikTok feed overrun with T*ylor Sw*ft. I guess I wanted to try something new. And fortunately for me, I didn't really need to worry: Kentucky Route Zero isn’t a game where you can win, or strategize, or even really change anything dramatically. This also means you can’t fail; you’re driving and your destination is fixed.

Though the game starts with the delivery driver, you slowly add people to your constellation: a talented TV technician, a kid who lost his parents, a couple devoted musicians. Eventually, there’s not really a sole protagonist. Your perspective as a player switches among these characters — you see what each of them could say, or be thinking about, in any given situation. It’s a direct line into their unfiltered thoughts, in that way; you can see the difference between which truths they keep hidden, maybe, and which ones they reveal.

As I was writing this I asked Matt if he feels, like I do, like driving makes his dialogue options limited. He said he thinks driving makes him a better conversationalist. “That’s when I focus the best,” he said. Maybe that is another way of saying it’s easier to find the truth?

Of course, in the game, nothing that’s said in these conversations changes the outcome. You’re still headed to your destination, to the story’s tragic-but-not-quite-tragic end. But the conversations do give the impression of changing how these characters feel about each other, and it changes they way you feel about the way it all unfolds. An NPR review put it this way: “The choices you make along the way don't matter at all, because we all end up in the same place. But then, the choices are also the only thing that matters, because it is those choices that create the story we're telling, and the one we're being told.” That feels true in a lot of ways to me.

(Oh, and also! The music —I could have written this entire newsletter about the music in this game. It’s magnificent, and was written and performed by Ben Babbitt, who you might also know from his work on Angel Olsen’s All Mirrors.)

Here are some other things I have been consuming lately: writing this essay about Yoko Ono and Kim Gordon and intimidation and expertise; Urban Driftwood by Yasmin Williams; the new Ovlov record; the new Courtney Barnett record; “Pain Without A Touch” by Sweeping Promises; weekly episodes of Succession with my family; The Final Revival of Opal & Nev by Dawnie Walton; cider doughnuts; risotto; this lemon olive oil cake I made for my family, which was so good; Swedish candy on a 24-hour trip to Brooklyn; a fake artist bio; Phil Morton’s 1976 experimental video art piece “General Motors,” which is referenced in KRZ; a PR on a seven-mile road race; “Self-Compassion”; one pumpkin spice latte on a Saturday morning and a renewed conviction that every suburban Starbucks barista in the world deserves a raise. (Plus, my cactus bloomed again! Just one small flower this time.)

***

This time last year I was: celebrating being in love and handing the mic to the best vintage seller I know.

***

Take care. See you on the Zero.

xo,

M

*except if you count the N64 my siblings and I had growing up, and the astounding and slightly frightening skill I developed at a Tetris-like game called Pokemon Puzzle League, which I can still play like a total champ. Really since then the only game I have played on Matt’s recommendation was Sayonara Wild Hearts, during lockdown, and that was mostly because of this essay my friend wrote about it.